Wind: mph,

Welcome to our new web site!

To give our readers a chance to experience all that our new website has to offer, we have made all content freely avaiable, through October 1, 2018.

During this time, print and digital subscribers will not need to log in to view our stories or e-editions.

A collegiate education has long been sold as a ticket to economic success. However, as the cost of living rises and student debt balloons to $1.6 trillion, this steep financial burden does not pay off equally for everyone.

That burden can be even higher for first-generation students who report higher levels of student debt and lower earnings after graduation.

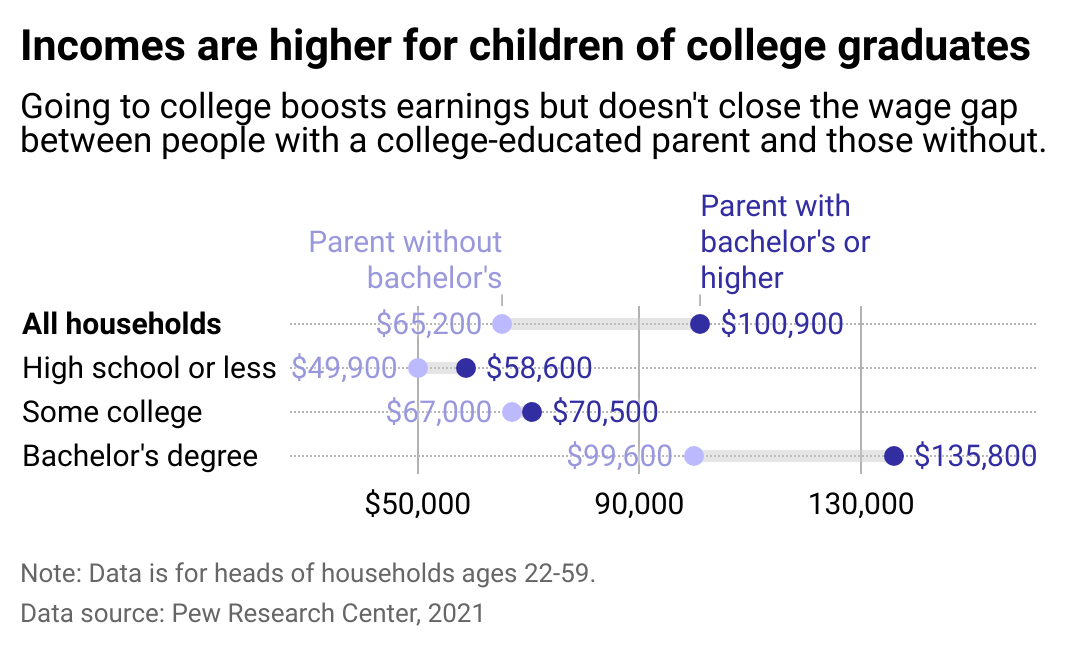

Bold.org examined Pew Research Center and the Federal Reserve data from 2021 to reveal earning disparities between first-generation college graduates and their peers. For this analysis, we define first-generation students as those raised by parents who did not earn a bachelor's degree, even if one of their older siblings did.

As of 2020, more than half of the undergrads in the United States were first-generation students, according to Center for First-generation Student Success data. However, despite representing a significant share of the student body, not all universities support first-generation students equally.

A 2022 survey of about 1,000 first-generation students from Inside Higher Ed and Kaplan found only about 1 in 4 strongly agreed their college helped them navigate college life.

For first-generation students, navigating an unfamiliar work environment, not having familial professional networks, and limited access to generational wealth can create compounding obstacles along their path to success.

Research has also found that first-generation students are more likely than continuing-generation students—or those with parents who earned a postsecondary education—to report symptoms of depression and anxiety in college while also being less likely to have access to mental health services.

For some students, the pressure of achieving success, combined with limited resources or institutional support, can present challenges in the collegiate environment and beyond. First-generation students are less likely to graduate college, but those who do face earning less than other graduates.

According to the Pew Research Center, a college education may boost earnings, but the gap between first-generation and continuing-generation graduates is over $35,000.

Even before graduation, first-generation students may face specific challenges that could impact their future earnings potential. Balancing their education and extracurriculars with part-time jobs, having the means to take unpaid or low-paid internships, navigating financial aid, and finding available grants and scholarships for college students are all aspects that can impact a student's professional profile and opportunities right out of college. These challenges are not necessarily unique, but first-generation students often lack the professional or family connections that give other graduates a competitive advantage.

First-generation students were also more likely than their peers to fall behind on student loan payments. In a 2019 survey led by the Federal Reserve, 1 in 5 first-generation students said they were behind on their loan payments—twice as many as those students with at least one parent with a bachelor's degree.

After graduation, first-generation adults' earning potential is limited by several factors, including less familiarity with the negotiation process and being more willing to accept offers quickly or accept jobs for which they are overqualified. Waiting for the perfect first job is a luxury not many recent graduates can afford. The Center for First-generation Student Success showed in 2017 that 7 in 10 first-generation students felt confident they could scrap together $2,000 for an unexpected need in the next month, compared to 4 in 5 continuing-generation graduates. This confidence fell to 55% for Black first-generation graduates.

More targeted efforts by schools to support first-generation students could curb some of these trends.

Targeted programs can help support graduates without the professional networks usually available to graduates with parents with higher education. They can also help close the earnings gap. Career centers have long been places where students can tailor resumes, prepare for interviews, and get general career advice. Some schools have organized specific workshops catered to first-generation students.

Other programs like mentorships, improving parent engagement, and first-generation graduate orientation can also help students become more familiar with the post-collegiate environment and better prepared after their diploma. Financial aid counseling is also key, with just under one-third of first-generation students saying they would like to see their school prioritize this service.

However, even with more institutional support, biases in the hiring process present an additional challenge. One study published in July 2023 in the Organization Science journal found that mentioning first-generation status in a cover letter could make candidates less favorable to workplace professionals. However, when employers are explicitly aware of the strengths of a first-generation background, they are more willing to consider these candidates.

Some of these strengths include resourcefulness, problem-solving, and determination. When presented to a group of college-educated workers, half of them considered offering the candidate a job. By contrast, when another group was told to think about the strengths of a first-generation candidate, without a prompt, only 1 in 4 considered the potential hire.

Peter Belmi, the study's lead researcher and associate professor at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business, emphasized the value of this "first-gen advantage," particularly as companies consider diversity, equity, and inclusion more consciously. "You want folks who, because of their backgrounds, can look at a situation and see different things," he told the Stanford Graduate School of Business. "Race and gender are crucial, but we should also think about diversity more broadly to include differing college majors, ages, career paths, and so on. First-gen is one of those things."

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Copy editing by Sofía Jarrín.

This story originally appeared on Bold.org and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.